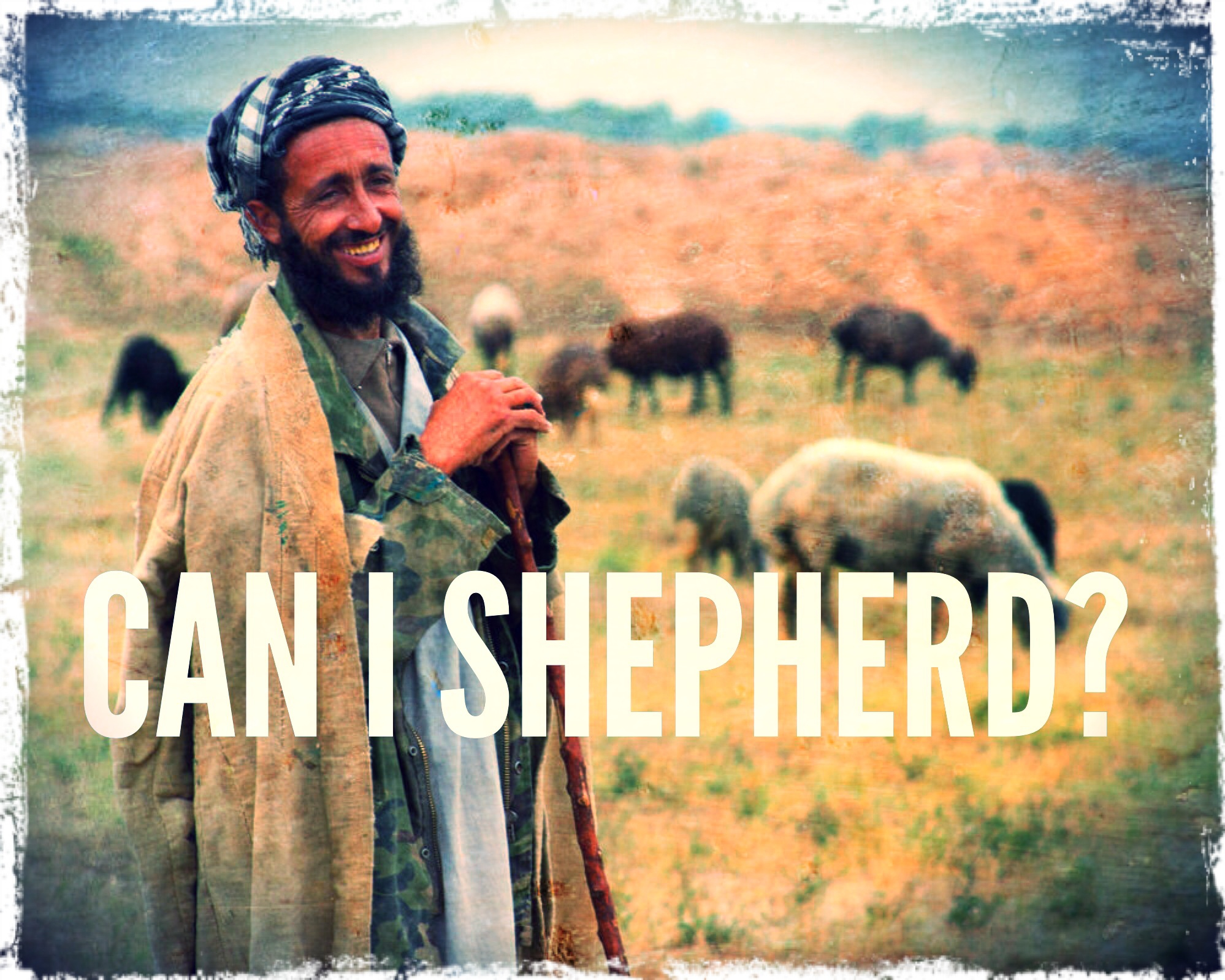

For some people, the word “shepherd” brings to mind watercolor paintings in church nurseries. The shepherd is cradling a lamb while the sun sets behind him in splashes of color. Or, he’s leaning on his staff looking out over a Crayola-green field. He’s got blue eyes and long wavy hair, his gaze is solemn, his robe spotless.

But when the apostle Peter used the word “shepherd”, his readers back then would picture a ruddy livestock worker. This guy is on the clock 24/7, scouting out pastures, corralling strays, dispensing first aid, fixing broken bones, making sure the sheep are safe and well fed. This dude works hard, gets dirty, and even knows how to go ninja with his staff.

When Peter tells to “shepherd the flock of God” (1 Peter 5:2), he has all this in mind. A shepherd of God’s people is responsible to care for them. He’s responsible to feed them the Word of God in his preaching, counseling, even everyday conversations. He’s responsible to protect the sheep from false teachers, from the poison of false doctrine, from the influence of the world. There’s a reason that “shepherd” is the most prominent metaphor in Scripture for a pastor’s role. “The fundamental responsibility of church leaders,” says Tim Witmer, “is to shepherd God’s flock.” Your success in ministry is always linked with their welfare.

But what exactly does it look like to shepherd God’s flock? It means several different things.

It means willing and eager oversight.

“Excercising oversight” (1 Peter 5:2) is actually only one Greek word: episkopeo. It literally means “to look upon”, and includes the idea of looking carefully or watching diligently. In his book Shepherds After My Own Heart, Timothy Laniak defines it as “a vigilant attention to threats that can disperse or destroy the flock.” The shepherd is a guardian with boots on the ground, ready to be used by the Chief Shepherd to guide and protect his flock.

It means love.

Practically speaking, shepherding means loving people. You can’t love ministry and be annoyed by people. The summons is a call to love sheep. “To love to preach,” Lloyd-Jones says, “is one thing; to love those to whom we preach is quite another.” A man summoned by God to lead his flock loves both. And both are essential to the task. The study and reflection required of a pastor isn’t meant to turn him into an academic hermit; instead his study must lead him to more effectively nurture the church. He must possess a basic capacity to communicate God’s heart and God’s love to God’s people.

It means connecting care to the Chief Shepherd.

The local church immerses shepherds in the stuff of life. Consider the mysteries of human experience – the childless couple who just had their third miscarriage, the new believer still entangled in a lifelong addiction, the hardworking provider who just lost a job, the dying sinner confronting the certainty of drama. In those despairing moments, who is appointed to guide God’s people through the inexplicable valleys to drink in the streams of God’s providence and goodness? Who will remind us that the Chief Shepherd is the Good Shepherd (John 10:11)? None other than the shepherds of the church. What a glorious display of God’s grace to create a special office for our care during times of trial and suffering. Far from the spotlights and media Christianity, caring shepherds labor in obscurity to tend people’s souls. They connect sheep to the Chief Shepherd.